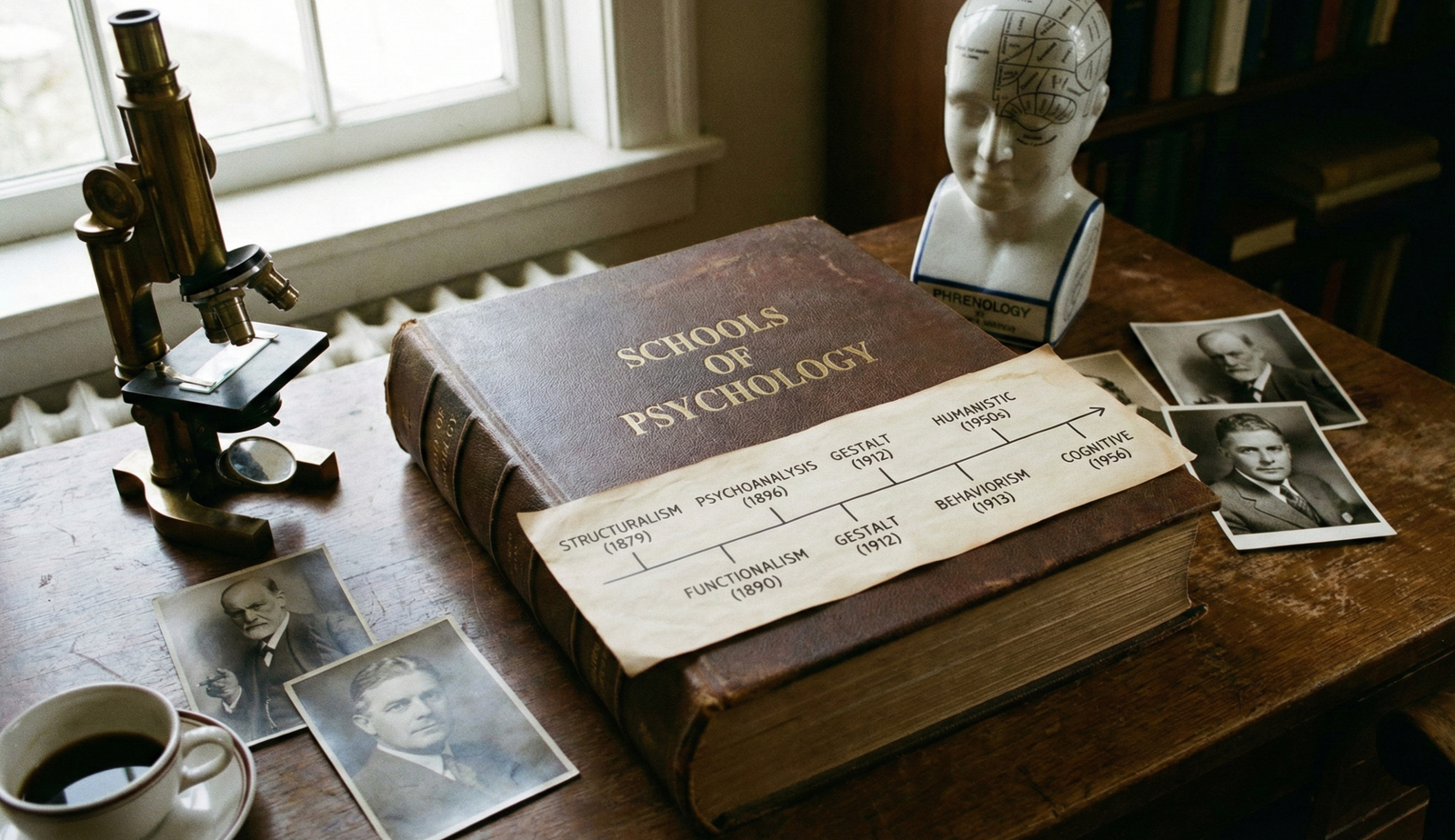

To deeply understand the foundations of modern mental science, one must examine the major schools of psychology that have shaped its evolution. At the university level, studying these schools of psychology goes beyond memorizing names and dates; it requires a rigorous analysis of the Zeitgeist (the intellectual and cultural climate of the era), the philosophical roots of the discipline, and the methodological debates that defined the field.

Before psychology emerged as a distinct scientific discipline, it existed at the intersection of philosophy (questions of empiricism vs. rationalism) and physiology (early psychophysics by Helmholtz, Weber, and Fechner). The transition from philosophical inquiry to empirical science gave rise to the foundational systems and schools of psychology we study today.

1. Voluntarism and Structuralism (1879 – Early 1900s)

While often grouped together in introductory texts, graduate-level study of the early schools of psychology requires distinguishing between Wilhelm Wundt’s original system and Edward B. Titchener’s later interpretation.

Wundt’s Voluntarism

In 1879, Wilhelm Wundt established the first formal psychological laboratory at the University of Leipzig. His system, known as Voluntarism, focused on the will, choice, and purpose of the mind. He sought to understand how the mind actively organizes fundamental experiences into higher-level cognitive processes (apperception).

Titchener’s Structuralism

Wundt’s student, Edward B. Titchener, brought a modified version of this science to America. Titchener discarded Wundt’s focus on active apperception and instead founded Structuralism.

- Core Tenet: The goal of psychology is to discover the structural elements of consciousness (sensations, images, and affections) and determine how they are connected.

- Methodology: Titchener relied heavily on systematic experimental introspection, requiring highly trained observers to describe the basic, raw elements of their conscious experiences without falling into the “stimulus error” (naming the object rather than the sensory experience of it).

- Critical Evaluation: Structuralism ultimately collapsed upon Titchener’s death. Its reliance on introspection was fundamentally flawed; it was subjective, unobservable, and could not be independently verified, leading to a lack of reliability in experimental results.

2. Functionalism (1890s – 1920s)

Functionalism was one of the first uniquely American schools of psychology, emerging as a direct reaction against the rigid, atomistic approach of Structuralism. It was profoundly influenced by the Zeitgeist of the era: Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution.

- Key Figures: William James (the philosophical pioneer), John Dewey (who applied functionalism to education), and James Rowland Angell (who formally defined the school at the University of Chicago).

- Core Tenet: Influenced by evolutionary adaptation, functionalists argued that psychology should investigate the function or purpose of consciousness, rather than its static structure. William James famously argued that consciousness is a continuous, flowing process (the “stream of consciousness”), not a collection of discrete elements.

- Impact and Legacy: Functionalism broadened psychology’s scope immensely. Because it focused on adaptation, it legitimized the study of animal psychology, developmental psychology (children), and abnormal psychology. It also birthed applied psychology, moving the discipline out of the laboratory and into clinics, schools, and workplaces.

3. Psychoanalysis and the Neo-Freudians (1890s – Present)

Developed by Sigmund Freud outside the traditional academic laboratory, Psychoanalysis arose from clinical practice in neurology and psychiatry, standing apart from other experimental schools of psychology.

Shutterstock

- Core Tenets: Psychic determinism (the belief that all behavior has a cause, often unconscious) and the primacy of early childhood experiences in shaping adult personality. Freud introduced the topographical model (conscious, preconscious, unconscious) and the structural model (id, ego, superego) of the psyche.

The Schisms: Neo-Freudians

Academic study emphasizes the fracturing of the psychoanalytic movement. Many of Freud’s followers broke away due to his dogmatic emphasis on infantile sexuality and biological determinism:

- Carl Jung: Developed Analytical Psychology, introducing the concepts of the “collective unconscious” and archetypes.

- Alfred Adler: Founded Individual Psychology, arguing that human behavior is driven by social interest and the striving for superiority (compensating for feelings of inferiority), rather than sexual drives.

- Karen Horney: Challenged Freud’s phallocentric views, emphasizing the role of basic anxiety and social/cultural forces in neurosis.

4. Gestalt Psychology (1910s – 1930s)

Developing contemporaneously with Behaviorism in the US, Gestalt psychology emerged in Germany under Max Wertheimer, Kurt Koffka, and Wolfgang Köhler.

- Core Tenet: A reaction against the elementarism of Wundt and Titchener, Gestaltists argued that conscious experience must be considered globally. The central maxim is that the whole is fundamentally different from the sum of its parts.

- Theoretical Contributions: They introduced principles of perceptual organization (figure-ground, proximity, closure) and the concept of insight learning (Köhler’s research with chimpanzees), which directly challenged the trial-and-error learning models of early behaviorists.

- Kurt Lewin’s Field Theory: Lewin expanded Gestalt principles into social psychology, proposing that behavior is a function of the person and their environment ($B = f(P, E)$), conceptualized as an interacting psychological “field” or life space.

5. Behaviorism: From Methodological to Radical (1913 – 1950s)

Of all the schools of psychology, Behaviorism staged the most hostile takeover of academia, arguing that the study of consciousness was inherently unscientific.

Methodological Behaviorism

Founded by John B. Watson with his 1913 manifesto, this early iteration argued that psychology must be a purely objective, experimental branch of natural science. Watson relied heavily on Ivan Pavlov’s classical conditioning, proposing that all complex behavior is a chain of conditioned stimulus-response (S-R) connections.

Neo-Behaviorism

In the 1930s, the paradigm shifted. Researchers integrated logical positivism and operationism into their frameworks:

- Edward Tolman (Purposive Behaviorism): Introduced intervening variables. He proved through his latent learning experiments that rats formed “cognitive maps” of mazes without immediate reinforcement, challenging strict S-R models.

Radical Behaviorism

B.F. Skinner returned to a stricter anti-mentalistic approach. His system of Operant Conditioning posited that behavior is entirely controlled by its environmental consequences (reinforcement and punishment). Skinner’s radical behaviorism denied that internal states (thoughts, feelings) caused behavior; rather, they were simply collateral products of environmental conditioning.

6. Humanistic Psychology (1950s – 1970s)

Emerging as the “Third Force,” Humanistic psychology arose to challenge the pessimistic determinism of Psychoanalysis and the mechanistic determinism of Behaviorism, carving out a distinctly optimistic space among the schools of psychology.

- Key Figures: Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers.

- Core Tenets: Grounded in phenomenology and existentialism, this school emphasizes free will, subjective reality, and the innate human drive toward self-actualization.

- Methodological Shift: Rogers developed Client-Centered Therapy, insisting on viewing the individual as a whole, conscious, and proactive agent rather than a “patient” to be diagnosed and manipulated.

7. The Cognitive Revolution (1950s – Present)

By the mid-1950s, the limitations of strict behaviorism became apparent. It could not adequately explain complex phenomena like language acquisition—a vulnerability famously exposed by linguist Noam Chomsky in his devastating critique of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior.

- The Catalyst: The advent of computer science provided a new, powerful metaphor for the human mind. The Information Processing Model suggested that humans, like computers, encode, store, retrieve, and manipulate data.

- Key Figures: George Miller (research on the capacity of working memory), Ulric Neisser (who formally defined the field), and Albert Bandura (who bridged behaviorism and cognitivism with Social Cognitive Theory).

- Current Paradigm: Cognitive psychology successfully brought the empirical rigor of behaviorism to the study of unobservable mental processes. Today, integrated with neuroscience (Cognitive Neuroscience), it forms the dominant paradigm of contemporary experimental psychology.

Conclusion

The evolution of these schools of psychology demonstrates that psychological science does not progress in a straight line. It advances dialectically—through thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. The structuralist’s lab gave way to the functionalist’s real-world applications; the behaviorist’s observable actions eventually required the cognitive psychologist’s internal algorithms. Today’s psychological landscape is fundamentally eclectic, demanding that graduate-level practitioners draw upon a synthesized understanding of these foundational systems to address the complexities of the human mind.

Student Assessment: Test Your Knowledge

1. Which concept was central to Wundt’s Voluntarism but discarded by Titchener’s Structuralism?

A) Systematic introspection

B) Apperception

C) The stimulus error

D) Empiricism

2. Functionalism was heavily influenced by the Zeitgeist of the late 19th century, specifically the work of:

A) Ernst Weber

B) Immanuel Kant

C) Charles Darwin

D) Hermann von Helmholtz

3. What critical error did trained observers in Titchener’s lab have to avoid, which involved naming an object rather than describing the raw sensory experience?

A) The apperception bias

B) The phenomenological error

C) The stimulus error

D) The functional fallacy

4. Which Neo-Freudian is responsible for the concept of the “collective unconscious”?

A) Alfred Adler

B) Karen Horney

C) Erik Erikson

D) Carl Jung

5. Gestalt psychologist Wolfgang Köhler’s research with chimpanzees directly challenged early behaviorist trial-and-error models by demonstrating:

A) Classical conditioning

B) Insight learning

C) Operant conditioning

D) Latent learning

6. The formula $B = f(P, E)$ represents which psychological concept?

A) Tolman’s Purposive Behaviorism

B) Lewin’s Field Theory

C) Skinner’s Radical Behaviorism

D) Rogers’ Client-Centered Therapy

7. Edward Tolman’s maze experiments with rats demonstrated that learning could occur without immediate reinforcement. He called this:

A) Operant conditioning

B) The phi phenomenon

C) Latent learning

D) Radical behaviorism

8. Which linguist’s critique of B.F. Skinner’s Verbal Behavior helped catalyze the Cognitive Revolution?

A) Ulric Neisser

B) George Miller

C) Noam Chomsky

D) Albert Bandura

9. Humanistic psychology emerged as the “Third Force” in response to which two deterministic schools of thought?

A) Structuralism and Functionalism

B) Psychoanalysis and Behaviorism

C) Gestalt and Cognitive Psychology

D) Voluntarism and Behaviorism

10. The Cognitive Revolution heavily relied on which technological metaphor to explain human mental processes?

A) The steam engine

B) The hydraulic pump

C) The computer (Information Processing Model)

D) The telegraph network

(Answer Key: 1-B, 2-C, 3-C, 4-D, 5-B, 6-B, 7-C, 8-C, 9-B, 10-C)